Last month, I discussed some useful tips on how to paint 3D printed plastic objects. Today, I will walk you through the painting process using an olive jar neck sherd from the Luna site. The sherd was one of the defining artifacts that helped UWF archaeologists recognize and establish the significance of the site. Below is my step-by-step guide on how to paint this specific artifact using the equipment and tips I outlined in my previous post.

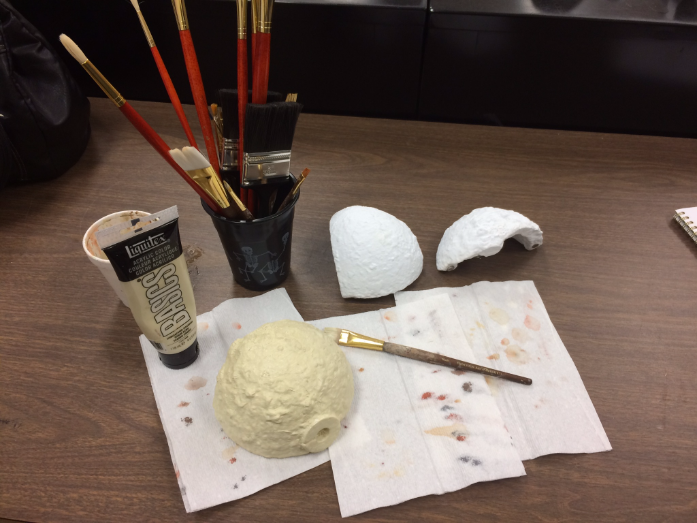

Here is my painting station, equipped with the colors I use for this artifact (minus two that I added in), paint brushes, paper towels, my “palette,” and a water cup.

Here is my painting station, equipped with the colors I use for this artifact (minus two that I added in), paint brushes, paper towels, my “palette,” and a water cup. - I start by adding a layer of unbleached titanium over the whole object.

- Then, I mix some paints to create the reddish color of the entire vessel. I use red and yellow to create a salmon color and add bits of Unbleached Titanium and Raw Sienna. I use the dabbing technique to create texture.

-

Colors used for gray. I mix the colors I use for the gray sides of the artifact. I obviously do this by mixing white and gray and then paint one layer on the sides. For a second layer of gray, I add a little bit of Raw Umber to the mix, which makes it slightly more brown. When I layer it on top of the light gray color, it creates depth and texture. There is also a line of gray at the bottom of the artifact.

- I do something similar to the entire object now. I add a little bit of grays and browns over the entire object to match the various tones and colors the artifact has in real life. I do this using a mix of dabbing and dry brush techniques and I try to be gentle and light about applying this layer.

- The final touch is to add a black detail towards the bottom corner of the concave side.

- This is the final product:

The final product is definitely not perfect, but it will do! Painted models, such as the olive jar neck sherd, can be implemented in educational demonstrations in classrooms, out in the field, in museums, or anywhere where archaeologists are able to interact with the public. I really hope that you enjoyed these blog posts about painting plastic artifacts and found some useful information. As always, feel free to respond with any questions or feedback.

Happy painting!

Mariana Zechini is a graduate student at the University of West Florida. She received her B.S. in Anthropology at Virginia Commonwealth University in 2014 and has four years of experience in 3D scanning archaeological materials. Her thesis focuses on analyzing stable isotopes from human remains from a medieval cemetery site in Berlin, Germany.